Democracy depends on citizens who can disagree productively. Professional success increasingly requires collaboration with people who see things differently. Personal relationships thrive when partners can navigate conflict constructively. Yet somehow, we expect people to magically develop these skills without ever really teaching them or creating spaces to practice them. The good news is that certain educational environments function as intensive training grounds for the art of disagreement, though rarely by explicit design.

The Impossibility of Silence

In a classroom of thirty-five students, a young person who prefers to avoid conflict can often remain silent, letting others carry the discussion forward. They can nod along, look thoughtful, and never actually articulate a position that might invite disagreement. This strategy works remarkably well for years, allowing students to graduate without ever really learning to voice dissent or defend a position against challenge.

In smaller settings, this luxury disappears. When there are twelve people in a literature discussion, everyone’s perspective becomes necessary for the conversation to function. Silence becomes conspicuous rather than invisible. Teachers notice non-participation not as one person in a crowd but as a missing voice in a small group. This visibility creates gentle but persistent pressure to participate, to take positions, and inevitably to encounter disagreement.

Watching Mastery in Real Time

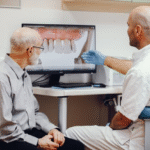

Small classroom settings allow students to observe how skilled adults handle disagreement. When a teacher facilitates a contentious discussion, students watch techniques unfold in real time: asking clarifying questions before responding, paraphrasing to ensure understanding, acknowledging valid points while still maintaining a different position, separating ideas from the people presenting them.

These observation opportunities are valuable precisely because they’re repeated and varied. Students see the same teacher handle dozens of disagreements over the course of a year, each slightly different, each requiring adjusted tactics. Many private schools Melbourne and elsewhere have built pedagogical approaches around this kind of modeling, understanding that students learn communication skills primarily through observation and practice rather than explicit instruction.

The Role of Vulnerability

Genuine disagreement requires vulnerability, the willingness to state a position that others might reject or ridicule. In smaller settings where students know each other well, this vulnerability is both harder and easier. Harder because there’s no anonymity to hide behind; everyone knows whose idea is being challenged. Easier because the relational foundation makes intellectual risk-taking feel safer.

Students learn that intellectual vulnerability, far from being weakness, is actually a form of courage and a prerequisite for learning. When they see peers take unpopular positions and defend them thoughtfully, they learn that standing alone on an issue is possible and sometimes necessary. When they watch classmates change their minds in response to good arguments, they learn that flexibility is strength, not capitulation.

The Teacher’s Delicate Balance

Facilitating productive disagreement requires skill and judgment. Teachers in small settings must encourage genuine debate while preventing discussions from becoming hurtful or personal. They must allow conflict without letting it spiral into damage. They must make space for unpopular opinions while maintaining basic respect and decency.

Students benefit enormously from watching this skilled facilitation. They learn what productive intervention looks like, when to step back and let disagreement unfold naturally, and when to step in with structure or redirection. These lessons in conflict management serve them when they later find themselves in leadership positions or parenting roles where facilitating productive disagreement becomes their responsibility.

The Long View on Conflict

Perhaps most importantly, students who learn to disagree well in educational settings develop a different relationship with conflict itself. Rather than seeing disagreement as something to avoid or as relationship-ending crisis, they understand it as a natural part of human interaction that can be navigated skillfully. They’ve developed confidence in their ability to handle conflict, to repair relationships after disagreement, and to maintain their positions while respecting others.

This fundamental comfort with conflict serves them throughout their lives, in contexts ranging from romantic partnerships to professional negotiations to civic engagement. They carry forward not just specific skills in disagreement but a basic belief that conflict is manageable, that relationships can survive it, and that the work of disagreeing productively is worth doing. These beliefs, learned through hundreds of small disagreements in classrooms where hiding wasn’t an option, shape how they engage with difference for the rest of their lives.